In June of 2018, trains on the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad followed their usual route: up and down Southwest Colorado, back and forth from Durango to Silverton. One morning, as the coal-powered locomotive barreled through the San Juan National Forest, several fateful embers floated into the air from the smokestacks. It was a seemingly inconsequential thing, something that neither conductor nor passengers would take much notice of. But when those embers landed, they would spark one of the largest fires Colorado has ever seen.

The 416 Fire blazed across the San Juan National Forest for over a month. By it’s containment on July 9, it was one of the top ten largest fire’s in Colorado’s history. But more notable than its’ size was the effect on the watershed that it surrounded. Hermosa Creek and the Animas River were flooded with debris, causing dire water quality conditions and suffocating fish for miles and miles of streams.

In some ways, rivers can benefit from wildfires. They maintain fire-adapted trees like aspens and pines along the river banks, which rivers need debris from in order to feed the bugs and other organisms within them.

“It’s a natural thing and our rivers and wildlife have evolved with that,” said Barb Horn, statewide water quality specialist and founder of the Colorado River Watch Program. “It’s really man’s impact that has made it worse.”

Regular intervals of low intensity fires will keep some sort of canopy along the riverbank. But fires that burn increasingly bigger and hotter from poor forest management and the effects of climate change can scorch everything in their path, leaving vegetation devoid “burn scars” in their wake. When a rainstorm comes, all the ash and debris from these scars heads down into the river.

The Animas is home to the Colorado native cutthroat trout, a species well-suited to the cold waters high in the mountains. But with a fire heating those waters and filling them with ash, a rare San Juan subspecies were threatened. That was when Colorado Parks and Wildlife stepped in.

With special permission from the U.S. Forest Service, Jim White and other members of the CPW embarked into the forest on ATVs to take fish from threatened streams to the Durango Fish Hatchery for safe keeping. White called this a last resort, as fish generally fare better in the wild than they will in a hatchery environment.

Rivers can usually flush out wildfire debris and heal well on their own. However, there were several factors that made the 416 Fire especially dangerous for the Animas inhabitants.

“Number one is that the Animas River was running at historically low levels,” said White, an aquatic biologist for CPW.

Fish populations can typically withstand debris and other water quality changes if there is enough dilution. But with shallower waters, ash and other particulates can clog their gills and suffocate them. The insects they eat get smothered as well, and the fish also lose the deeper, cooler waters that they need to spawn. This leads to “dead zones” in rivers where neither fish nor their smaller prey can thrive.

“We ended up doing two rescues, one before the fire actually encroached onto the stream and then one post fire,” said White. The exact location of these rescue missions was withheld for the safety of the fish.

Rainstorms in the wake of the the fire devastated the Animas, with a recent Colorado Parks & Wildlife survey estimating that it lost 80% of it’s fish population following the fire. Fish kill was evident as high up as 10-15 miles in the Animas, and as far south as the New Mexico and Colorado border.

One unexpected outcome of the 416 Fire on the Animas was an unprecedented spike in metal concentrations.

“We knew from other fires that there can be elevated metals,” said Scott Roberts, water programs director for the Mountain Studies Institute in Durango. “But it was extraordinary for our river.”

The Mountain Studies Institute began monitoring the Animas River with more intensity after the Gold King Mine spill compromised the waters in 2015. In a post 416 Fire study, they found a clear correlation between deteriorated water quality and runoff from burn scars, with some samples of metals like aluminum, iron and mercury exceeding those from the Gold King Mine incident, in which mine drainage turned the water burnt orange.

While Roberts said that the levels of aluminum and iron could be explained by the natural geology of the area, the mercury levels are a bigger unknown.

“We don’t typically see a lot of mercury in our fluvial systems,” said Roberts.

Though some things about the 416 Fire, were unique, it is certainly not the first wildfire in Colorado to devastate water supply.

An act of arson on June 8, 2002 grew into a blazing 138,114 acres, the largest fire in the state’s history: the Hayman Fire. Beginning between Colorado Springs and Denver, the Hayman Fire reached Cheesman Reservoir on its second day, which over 1 million people in Denver rely on for their water supply.

Denver Water would spend over a decade and $27 million trying to clean up the effects of the Hayman Fire, including extensive water quality treatment and sediment removal. Cleaning up drinking water following a wildfire comes with particular challenges. The organic carbon released from the soil during the fire reacts badly with chemicals used to purify the water, resulting in carcinogens instead of clean water.

If it took over a decade for the Cheesman Reservoir and surrounding streams to recover, how long should we expect it to take for Hermosa Creek and the Animas to clear up?

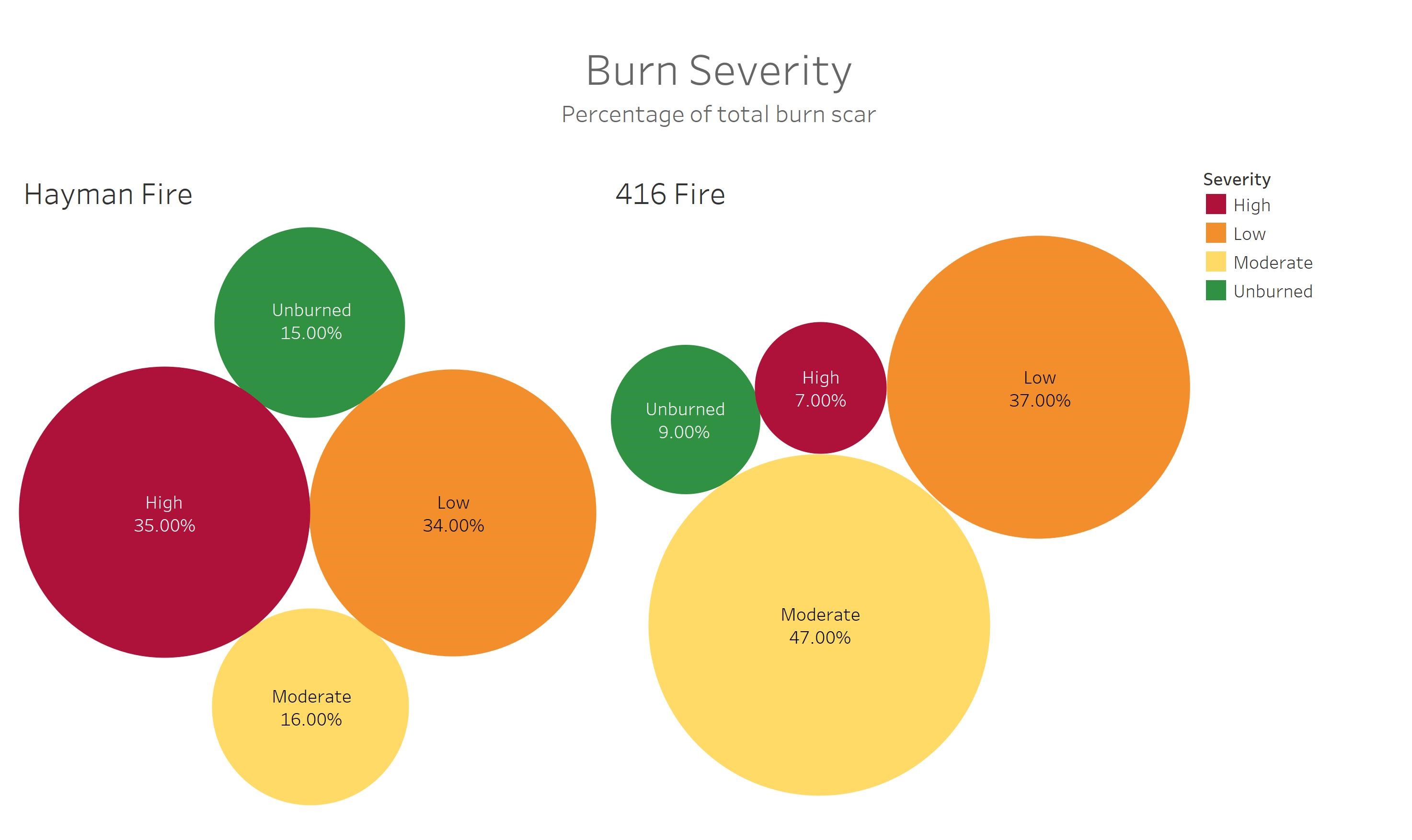

Burn severity may play a huge part in the timing of this recovery. It is generally defined as the loss of or change in organic matter aboveground and belowground. The U.S. Forest Service Burned Area Emergency Response program uses satellite data to determine the loss of vegetation post fire. “Unburned” represents areas with healthy, average vegetation, while “High” indicates a large change in vegetation.

Researchers looked at historic fire data and found that the Hayman Fire burned with a severity that was unprecedented for the area in the last four centuries.

According to Horn, the Animas will recover gradually on its own as the seasons change. Snowfall from the winter months will help flush out the pollution in the spring.

“The only mitigation is Mother Nature,” Horn said.

Sources

Fire Perimeter Data: USGS, https://www.geomac.gov/GeoMACKML/getKML.aspx#

Burn Severity Data: U.S. Forest Service Burned Area Emergency Response program

Map Icons: https://icons8.com/

Photos:

- U.S. Forest Service (via Inciweb and Twitter)

- NASA Johnson, Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

- Bryant Olsen, Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

- Alex Rockwood, Wikimedia Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

- Photo_Hiker_Dave, Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/